Baiq Asmini lives in Arubara, Ende Regency, Indonesia and has been an octopus data collector since 2019. She works with octopus fishers in Arubara to record their catches, enabling them to start understanding more about their octopus fisheries.

It has been an amazing journey for me, working together with octopus fishers and buyers in Arubara,” said Baiq. “It started when Yayasan Tananua Flores (Tananua) introduced me to participatory fisheries monitoring. So, usually, me, the octopus fisher and buyer will do the data collection either in the landing site when a fisher comes back from the sea, or at the buyer’s house,” she added.

Since 2019, Tananua has been assisting octopus fishers in Arubara sub-village and the neighbouring Maurongga village to monitor their octopus catches. Tananua is one of Blue Ventures’ partners in Indonesia that we support in collaboration with Yayasan Pesisir Lestari.

Indonesia is among the top 10 global octopus exporters, with an export volume of around 19,000 tons/year and average value of $90 million USD/year, and demand continues to increase. This demand is putting extreme pressure on the species and their survival. However, there is no national management plan in place for the fishery; without management the fishery is likely to be overexploited. That’s why participatory octopus fisheries monitoring is important, as the data can empower small-scale fishing communities to manage their fisheries more sustainably.

“We record the fisher’s name, fishing location and time, the total of octopus caught, and details on the octopus like mantle length, sex, weight – and we write them all in the book,” said Baiq. “When the catch is abundant, it could take a whole day to input data to the book!” she added.

“I have been learning a lot about octopus fisheries for the past two years. I learned about how important it is to understand Arubara octopus production at different times. Is it increasing, or decreasing? When is the most productive time? This will give us an understanding about fishers’ income, too,” she explained.

And recently, I learned something new: collecting data using a mobile phone,” said Baiq.

In April 2021, Baiq became one of three data collectors in three different communities to begin mobile octopus fisheries monitoring. They were trained by our partner organisations: YAPEKA, Tananua and JAPESDA.

Training partners in mobile monitoring

In collaboration with Pesisir Lestari, we have trained a total of ten community-based partner organisations on how to transform paper-based data collection systems into mobile systems. The COVID-19 pandemic has meant that the training was conducted remotely using an online meeting platform.

We’ve had to make many adaptations due to the pandemic, but transitioning to training partners online has been one of the more positive changes. It’s much more flexible and means we can train more people in one session. Whilst we miss the hands-on nature of in-person training and have faced some issues along the way, such as poor internet connections in field sites, the online training has been a success.

From the process so far, we’ve learned that online mobile monitoring training takes time. Having several sessions was very useful so the participants could learn step by step. After each training session, our partners had the chance to put their learning into practice – after all, the best way to learn is by doing. Simulation or role play are important tools to give a full understanding of the process before actually deploying the system in the field.

After several training sessions, the mobile fisheries monitoring system is now in place and ready to be implemented by the communities. Three of our partners, YAPEKA in North Sulawesi Province, Tananua in East Nusa Tenggara Province and Japesda in Central Sulawesi Province have already trained the communities they support in using technology for octopus fisheries data collection.

Shifting to digital

For the past three years, I have been training communities in participatory fisheries monitoring and I see their enthusiasm growing all the time. I am very humbled to see how the communities are becoming the main actors in fisheries monitoring and I have witnessed how proud community data collectors are when they show me their books containing the data they’ve collected and carefully written up.

The tools used for paper-based octopus fisheries data collection are simple: a book, a pen, a scale and a ruler. This system is affordable, hands-on, easy to do, and builds a basic understanding of the data collection process. The data can also be easily stored by communities themselves.

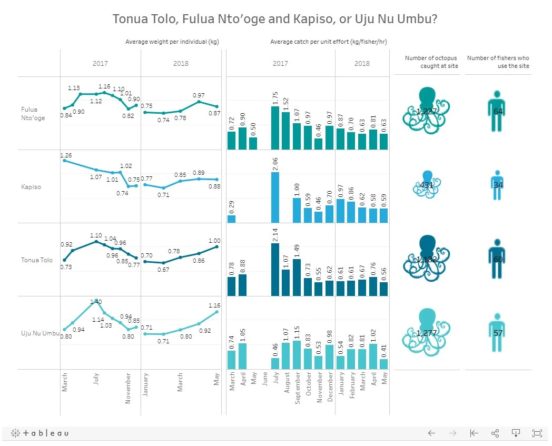

However, paper-based data collection also has some disadvantages. It requires a longer period for data entry into the online database system as we (or our partners) can only help communities to do this on a monthly basis. Once data is uploaded online, we use a tool called Tableau to create accessible visualisations of the results, which can be presented back to the communities. For fisheries management purposes, the faster real-time data can be analysed and fed back to the communities, the better, so that they can make fisheries management decisions in a timely manner.

In the past few years, technology has been developed to improve fisheries monitoring for many species – this includes using devices like mobile phones or tablets for data collection to replace the paper-based system. Mobile fisheries monitoring has a number of advantages: it’s paperless, introduces the use of technology to communities and may be more appealing to young people. Crucially, mobile data collection is also much more efficient when it comes to data management; the data is immediately uploaded online, which means that communities can see visualisations of the data much quicker and therefore make timely and informed decisions about their fisheries.

In North Sulawesi, East Nusa Tenggara and Central Sulawesi Province, the community data collectors are enthusiastic about learning new things, however, the project is still in the very early stages. Together with our partners, we are observing and learning to find the best practices. For example: is the mobile system lengthening the data collection process? After measuring the octopus, the collector needs to clean and dry their hands and then input the data to the mobile device so as not to damage it.

Hopes for the future

At the start of the process, community data collectors must be assisted on a daily basis until they are familiar with the new system. We continue to provide learning experiences for both the partners who assist the communities and also the communities themselves.

“Data collectors, together with Tananua, keep reminding the fishers, buyers, and the community about the importance of this participatory fisheries monitoring. Usually I say, the more we know about octopus production in each fishing location, the better a fisher can prepare so that they won’t come home empty handed,” Baiq said.

For this transition process into mobile monitoring, we will learn it step by step. When the fishers can really understand how to take care of the ecosystem, the octopus catch will be more abundant in Arubara.”

In the upcoming months, more of our community-based partners will be trialling mobile fisheries monitoring. We are very excited to learn more and gather insights from the field to improve the process. Watch this space…

Learn more about using online tools for training partners in Indonesia